http://www.msi.org/articles/5-things-i-know-about-marketing/

This link contains great articles to read; very informative.

The article below is from Susan Fournier:

1. Brands are a means to an end, not an end in themselves.

As brand managers and branding researchers, we put brands at the center of our thoughts and activities and in doing that, we lose perspective. We have supermarkets brimming with 60,000 SKUs and literally thousands of brands. Every brand manager thinks that their brand plays or could play a big role in people’s lives. That is not—and simply cannot be—the case!

People are social animals; at their core they are all about relationships with others. Our families, our friends, our coworkers—that’s what drives us. Brands sometimes play a role in that, but no matter how you slice it, they are the means in people’s lives, not the ends.

Brands can be a means to get the kitchen cleaned, which is just something I do as a mother with an Italian heritage, or they can be a means to express a certain vision of myself, an identity that matters to me, or a role I want to perform well. The key word is “can”.

Very often, brands are totally in the background. Maybe John likes to bike, and he is part of a biking club and he goes out every Saturday and participates in races. For him, it’s about the community of bikers. The bike is there; he enjoys it, but the point of this brand relationship is the people that he is riding with. His Cannondale is a means to that end.

To advance brand strategy, marketers will typically do a category study—map the attributes and benefits of, say, Minute Maid versus Tropicana versus Simply Orange—and act as if this brand-defined context is what the world is all about. Well guess what? It’s about the people, not the brands. If we want strong brands we have to start with a deep understanding of the people and figure out where our brands fit into their lives, if at all.

2. Our approaches to customer development are very simplistic (and big data may actually hurt and not help).

We take a really shallow view of customer development. Brand managers try to move people in aggregate groups along one path, typically from shallow to deeper. Did you buy more? Are you with us longer? Do you advocate for the brand among your friends? But there is a lot more going on than progressive layers of loyalty and commitment.

Ironically, big data can thwart the mission to develop more inspired customer development plans. The analyst’s job is to reduce everything to 0’s and 1’s. To take out context that can complicate things. To reduce the data to empirical relationships with correlations like, “People in zip code X tend to buy peanut butter sandwiches.” But this is information without meaning. We are overly enamored of information when we need to be focused on meaning. This complicates things, but no one said it would be easy.

3. The brand is what the brand does; brand meaning is complicated.

Everything we do affects the brand meaning and hence the brand relationship, whether it is in the brand strategy or not. Marketers might send out coupons or a survey; their intent is clear—to ignite purchase—but this is a meaning-laden signal and people may interpret this signal in completely different ways. For one person the coupon says, “You really don’t care about the important things in this relationship”; for another it validates the tit-for-tat nature of a basic exchange.

Brands and the organizations that represent them leak signals constantly. When Martha Stewart told Barbara Walters that her alleged illegal sale of ImClone stock was meaningless, insignificant, and represented a mere fraction of a percent of her personal financial equity, she created brand meanings that certainly did not help her brand. Unintended signals can stand as big statements about what the organization believes in or doesn’t believe in, and fundamentally affect the brand at its core.

Marketers do tons of work to figure out a brand’s positioning and they spend millions of dollars communicating and reinforcing that. To make things tractable, they want to circumscribe brand meaning and put it in a box: “This brand is the [blank] among all [blanks] because it [blanks].” But when a brand gets into a person’s life, there isn’t consensus about what it means. Multivocality and co-creation are terms that have been used: a brand speaks with many voices.

My doctoral student Claudio Alvarez has shown empirically that brands have less shared meaning than they have idiosyncratic or personalized meaning. Yet, our entire branding philosophy is founded on the task of finding one differentiated meaning and repeating it until everyone develops shared knowledge and familiarity with that positioning. Things would change radically if the paradigm was refocused to encourage idiosyncratic meaning.

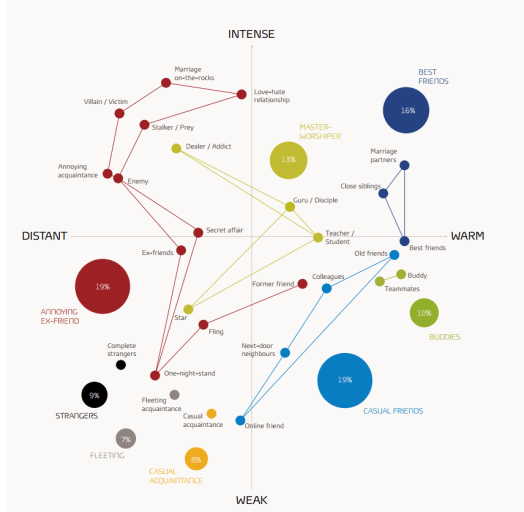

4. Marketers underappreciate the importance of brand relationships that are not “marriages”.

Basic exchange relationships are the most prevalent form of relationality in the commercial space. Yet we are always trying to move beyond them. I think there is a lot to appreciate in basic exchanges, especially because habits are often involved. Habits run deep and our understanding of them is shallow.

Or consider brand flings, which we also dismiss: “Oh, that’s bad, the consumer played with us and then they moved on.” No, that’s awesome. A fling has tremendous passion and an amazing amount of investment. You’re obsessed; it’s all-consuming. Yet we always want to move people out of flings into brands marriages.

Just think about a situation where 100,000 people are having a fling with your brand this year and another 100,000 people are having a fling next year. You can run a whole business on that! Get more people to have flings and then maybe have a product portfolio so they can go to another brand and have another fling when the passion dwindles. Embrace it—it’s beautiful stuff!

Marketers also tend to ignore the negative relationships that likely populate their brand relationship portfolios. In cross-cultural research with GfK, we learned that on average 45% of a brand’s relationships are negative. Yes, we have some insight into managing service failures, but that does not constitute a science of negative relationships. Abusive marriages, enemies, ex-friends, addictions, stalker-prey. These are the relationships that can make or break you. Do we know how to manage them? To think you can turn these into brand marriages is optimistic at best. These relationships each need to be dealt with on their own terms. What are the rules of these relationships? What meanings are being sought and delivered in the brand? Those are questions we could be asking. You can create interesting segments with that data and craft strategies to migrate people across relationships in your brand’s relationship space.

5. Risk is elemental as a brand construct.

In marketing we are revenue-centric; we don’t think a lot about risk. But risk is a huge part of branding. People stick with a brand to control risk: psychological risk, financial risk, the risk of failure. In stewarding a brand, the manager’s job is to understand risk and manage accordingly.

In a project with my BU colleague Shuba Srinivasan, we analyzed ten years of data on brand architecture strategies—for example, Fed-Ex and its “Branded House” where everything is branded Fed-Ex, or Apple’s sub-branding strategy with the Apple iPod, or endorsed branding as with Courtyard by Marriott, where two brands are combined and the secondary brand is prominent. We learned that some of these strategies are inherently riskier than others: there’s risk of meaning dilution, risk of reputation loss in the wake of failures, cannibalization risk, and financial risk from lost opportunities or competition for management time. When you factor in risk, the standing recommendations for certain strategies change. Sub-branding, most notably, exacerbates rather than controls risk.

“Person branding” is another interesting scenario where managing risk—the risk of personal crisis, the risk of death—is more elemental than managing revenues and returns. Think of Taylor Swift, Martha Stewart, Tiger Woods, and even Barack Obama.

We could rethink the entire exercise of branding as risk management. It reframes everything. Do we have the skill sets and conceptual frameworks to migrate to risk management? I do not think so.

http://www.msi.org/articles/is-your-brand-a-partner-a-best-friend-or-a-secret-affair-for-your-customers/